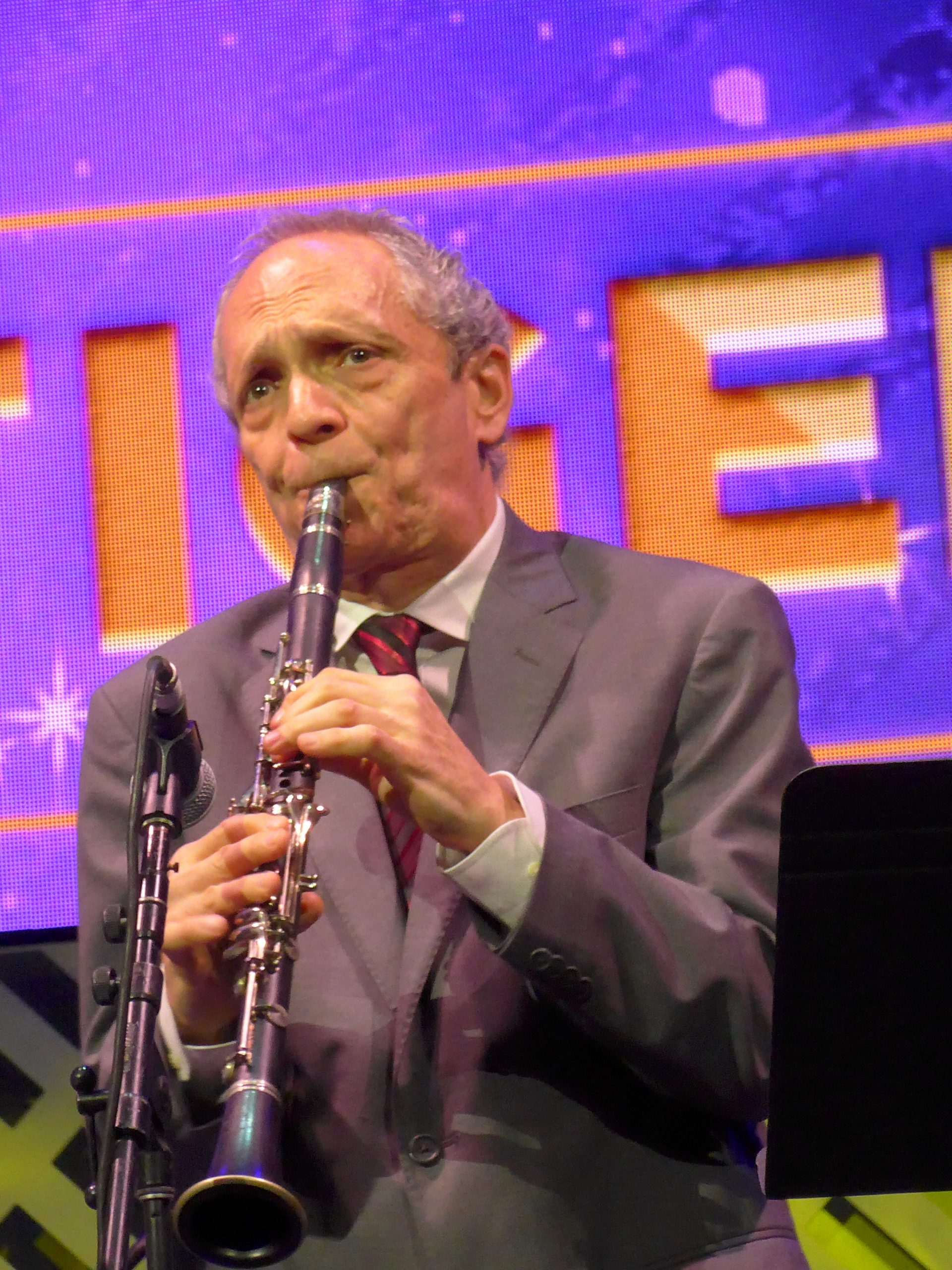

One of the leading clarinet and tenor sax players on the US jazz scene, Ken Peplowski (63), had to face hard times during the last four years. First a divorce, then not being able to travel, play and earn money during the pandemic, and then diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. Jazz Podium’s Hans-Bernd Kittlaus could talk to him on the Jazz Cruise in the middle of the Caribbean in January 2023.

HBK: How are you doing, Ken? The way you have been playing here this week you don’t sound like you are sick.

KP: Well, I appreciate that one. I feel stronger every day, honestly.

HBK: Your concert with Shelly (Berg) last night was so wonderful. And it was very moving when you talked at the end about your condition.

KP: I meant it, you know, so many people on this ship helped me out in every way financially. And the United States, we’ve got nothing, you know? No free healthcare. No unemployment help for self-employed people. And during the height of the pandemic, we got a special, one time only, like six months of just like $1,500 a month. And that was it, you know? As I’ve never taken a teaching job as so many musicians, you want something to fall back on. But I was lucky, and I had all this. You gather momentum after 40 years of traveling and then three years, and then you feel like you’re starting all over again.

HBK: Yeah. I saw that on the internet. You raised something like a hundred thousand dollars.

KP: Yeah. Unbelievable.

HBK: Let’s talk about your plans. What is it that you want to do next in terms of music?

KP: Recording. So in immediate future next month, I’m doing a live recording with the drummer Willie Jones III. Really great drummer. Plus Martin Wind and Ted Rosenthal. And we’re recording at Smalls.

Usually, my home in New York is Birdland. I play two regular weeks out of the year, and then come in sometimes for other things. But the guy at Smalls said, come in, do a live record. I know you’ve been through some rough times, and I’ll pay you a good fee for it.

I’m in full remission now and I’m ready to work. So promoters get out there and hire me. Cause I wanna play, you know, I’m coming back on the scene again. In the fall, I am going to do a tour in Europe.

During the pandemic, I did it like everybody else. I did a year of a streaming show. The hook to the show was I never repeated a song for the whole time. So after a year, I thought this is too much work now. And I started getting some gigs back too. I think I did a total of 48 weeks with maybe at the most five repeat songs. You’ve seen the show. I did research, and spoke for 10 to 15 minutes up front about the history of the songs and songwriters. So it was a lot of work, but it helped me because it felt like I was working, you know, through that.

There’s a lady on this ship who sponsored the show in the sense that she covered the musician’s fees, the cameramen and the audio person, which is why they look good and they sound good. So when I get back home, we’re gonna get together and start putting out a kind of best of, and offer them for not much money, but for sale.

HBK: I am sure you are the guy on the ship beside Houston Person who knows the most songs.

KP: I always like to push myself and enjoy the challenge for myself. And even more so if my back is against the wall, you know? I’ve got a huge repertoire, just like Houston. We’re like brothers. He and I talk at least once a week, and he’s a fascinating guy. Loves to talk politics and books and stuff. On stage, you don’t get any of this cause he almost says nothing, you know? But he’s a really interesting guy.

HBK: You have always played clarinet and tenor saxophone. What do you consider as your first instrument?

KP: Well, literally the first instrument was the clarinet. So it’s like the first love, you know. It is a more demanding and unforgiving instrument. So you have to stay on top of that. But I could never give up the saxophone because I like the two different voices. And even when I’m choosing songs, I hear a specific instrument in my head. And I might try just to again challenge myself, play something that’s known as a saxophone song on the clarinet and vice versa.

HBK: How do you see the situation of the clarinet in jazz? I mean, when you started some 40 years ago there were not that many clarinet players.

KP: No. Benny Goodman was still there. I worked in his last band, actually. But you’re right. There’s more coming up now again. And I do have a theory about that because if you follow the jazz timeline, there was a period where the music became very electric and loud. And for lack of a better word – I hate all these terms – fusion jazz. The clarinet is not an instrument that can cut above an electric band, or even a loud band. It’s just not capable of that. And I’m not a loud player. So now there’s more of a return back to acoustic jazz again. And that’s why we’re seeing more clarinet players again.

HBK: So who would you see as the next generation on clarinet?

KP: Well, there’s people like Anat Cohen. There’s this guy Adrian Cunningham, a really nice player. I promise you, in the next decade you’re gonna see a lot of fresh faces, you know

HBK: Let’s go back a little bit. Your name is pronounced ‘Peplauski’ in the US. It would be pronounced ‘Peplofski’ in Germany.

KP: Yes. Well, it should be that way in America. <Laugh>. But I think it was so mispronounced all the time that the family just gave up a long time ago. So it’s Peplauski to everybody else. But if you say Peplofski, I love it.

HBK: I guess it comes from Poland.

KP: Yes, it does. My grandparent on my father’s side came from Poland. I wish I learned the language. My father’s generation was that generation that were proud to speak English. But my brother and I had a Polish polka band, and he would teach us the words phonetically. So we sang in perfect Polish, but then people would start talking to me in Polish, and I had no idea what they were saying.

HBK: So how does somebody who plays in Polka bands get into straight-ahead jazz?

KP: Well, that’s a good question. Believe it or not, that specific type of polka, the Polish Polka is unbelievably similar to New Orleans Jazz, because the clarinet improvises mostly kind of arpeggiated stuff, like early New Orleans Jazz, like Jimmie Noone would do, or Johnny Dodds. And there’s two trumpets playing together, like King Oliver’s band. And then every song – just like the New Orleans songs – has three or four parts and then sometimes a key change, and then you improvise on that part. And then sometimes there’s even a four-bar drum break at the end. So I learned to improvise cause I did my first gig at age 11.

Then I actually took the Berklee School of Music, had a correspondence course for a while, which was quite good. They’d send you each week a lesson in harmony and music theory. And I would do that. I was 11, 12, 13 years old, so pre-internet days. You’d send back the papers and they would grade it or make comments. But I’m glad I learned that way because even now, I tell students, don’t get too hung up with these thousands of method books because all of them are correct in their own way. Yet all of them are also incorrect in a sense. Because in jazz, there’s no real hardcore rules that you have to follow. They wind up thinking if every student learns the same system of playing they’re gonna sound similar. They think, okay, if I’ve got this chord, I’ve gotta play this scale. I must play these patterns. But that’s just not true. And as I say to them, why do you like somebody’s playing? It’s because they have their own style and their individual sound. So it’s good to learn all that knowledge, but just remember, take what you can get from that, but forge ahead and figure out your approach. They don’t teach that in schools, to just try stuff, just play by instinct. Sometimes, I tell them, record yourself. Then you can analyze the recording afterwards, and then you can figure out, okay, why did this work? Why didn’t this work? I quote a phrase that Dizzy Gillespie supposedly said once when he was talking to students. He says, don’t worry about it. He says every phrase you play, you’re one half step away from salvation <laugh>, because sometimes it’s just about how you resolve the phrase at the end. That makes it a right note versus a wrong note, you know? Yeah. And you can go as far back as Lester Young who could play atonally sometimes, but he’d play a quote unquote wrong note and then repeat it, just to let you know, yes, I meant to do that <laugh>, and here it is again.

HBK: That’s what Gary Bartz likes to say. He does not improvise. He composes on the spot. The only situation where he improvises is when he made a mistake. <Laugh>.

KP: That’s good. I like that. That’s actually a good attitude. Because the goal is you learn the song and then you should forget it. If you’re still thinking about each chord change, you’re putting an automatic time delay in the brain, you’re just lagging a little bit behind or playing a little too carefully. You gotta learn a song well enough that when you’re up on the bandstand, you’re just not even thinking. You just kinda let your subconscious take over.

HBK: So that was the bridge into jazz when you did these Berkeley things?

KP: Well, no, I’ll go back a little bit further. The bridge into music was my parents took my brother and I to see “A hard day’s night” in the movie theater, 1964, I was five. And I still remember to this day, people in the audience screaming just to see them on stage. And I looked up there and I thought, I’d wanna do this somehow. Well, not being the Beatles – although I’m still a big fan. That made me wanna play music. And hearing Duke Ellington’s Band, I first heard this record, the Great Paris concert. It’s a fantastic record. Listening to Jimmy Hamilton just blew me away because he played like a symphony orchestra player. He had that beautiful dark classical sound. And even the way he played it was all correct. Like, he wasn’t flailing around, he just kept his fingers close around the clarinet. So he really impressed me before Benny Goodman. And I got to meet him later on. As an aside, he came to New York and played a couple of times, and I was almost crying, just talking to him. And he was a very nice, very kind person.

I talk about this freely now. Everybody complains, oh, I had a rough childhood. I did. My father was a kind of bigoted cop in Cleveland. A lot of daily beatings from both parents and arbitrary punishments. It was pretty tough. So even as early as I would say, five, six years old, I, I was drawing inside of myself and thinking, something’s gonna get me outta here one day. And it was music. That kind of saved my life really.

HBK: I guess we are talking about the seventies, right? When straight-ahead jazz was really in a situation where there was the danger that it would disappear. So why did you choose that?

KP: Well, because I never considered myself a great composer of songs myself. I was never happy with the stuff I wrote. So I thought my vehicle would wind up being those older classic songs to the point where you think to yourself, if you’re playing a George Gershwin song, why does it have to be the obvious 10 songs that everybody performs? When he wrote over a thousand, and the same of course with Duke Ellington and Strayhorn, you could spend a lifetime playing those songs. And on almost every album I’ve done, I try to include at least one of their songs cause they meant so much to me. Those two great bands of his, the Ben Webster years and later the one with Sam Woodyard and Jimmy Hamilton, both of those bands just blew me away. I’m a fan of that kind of music and there’s so much out there. It’s a treasure trove of music that people haven’t recorded.

Houston and I have this in common too. We both have massive collections of old sheet music song books. I’ve got a storage room in Manhattan that I go into. I’ll open up another box, pull out the music. So I’m constantly finding new things, but I tell the rhythm sections I work with just because it’s a song from 1930, I don’t want you to just play in what you think is a swing style. I’m hiring you cause I want you to play the way you play. And I like to play that music with a little more freedom and openness. So it bugs me sometimes when people always refer to me as a swing player because I love Ornette Coleman as much as I love Charlie Parker or Benny.

HBK: We were in your teens. So what happened next?

KP: Well, so then I started playing jazz and meeting older jazz musicians around Cleveland and sitting in. Technically, I was born in Garfield Heights, Ohio. So that’s southeast of Cleveland, but only a 20 to 30 minute drive. There never were a lot of jazz clubs in Cleveland. The joke is you come from there. But I started doing more and more jazz, dropped out of the wedding party band, focused on that.

Went to college for just two years. Not a great college, it was Cleveland State University. But I went there because I’d been studying with a wonderful clarinet teacher, and I wanted to keep studying with him. Then I played this jazz festival in Cleveland, and we were the Cleveland Band. They had Teddy Wilson’s Trio, actually, and I got to sit in with him. I introduced myself and he said, well, come on down and bring your horn. That was a frightening experience. As he got older, he had arthritis problems, but still just to play with him was a thrill. And the Tommy Dorsey band led by trombonist Buddy Morrow, they heard me play, and took my phone number and asked if I’d like to come on the band.

And this was how cruel my parents were. They called my house like the next week. And my mother took the call and never told me about it. Luckily, they persisted. The road manager called, a month later, I picked up the phone and he said, you know, Buddy really wants you to come on the band. You would play Lead Alto, and he wants to give you like a 15 minute feature spot on clarinet. And I jumped at it. I said, I’ll be there, when do I join? And within I think a month I was out on the road with that band. Not only did they give me features upon clarinet, but then he started having me do standup comedy to the audience, which usually bombed horribly <laugh>. But again, when I feel any kind of negativity like that, it makes me even work harder. I’m thinking, pardon my French, I’m just gonna keep telling these jokes. I don’t care. And I was making the band laugh, which counted more in a way, you know.

Buddy was so kind to me. And I stayed on that band for two years. And those days we were still out there 48 weeks out of the year doing a whole lot of one-nighters. I was 20. In those days, that was the alternative to college, and usually the better alternative. So all the big bands were still around. So that was most players‘ goal, to find one of those bands. Because there’s nothing like that discipline of playing every night. And sometimes you’re playing the same charts and on this one you get an eight bar solo, over here, you’re playing the bridge. And so you’ve gotta learn how to make it count. And also, the band personnel shifts all the time. So you gotta tighten up the saxophone section. So my thing was, you never stop trying to approve the arrangements. Just for boredom’s sake, otherwise it would get tedious, you know? So you’re constantly finding, okay, what can I do to make this better? What can I do to make this tighter? So that was a great discipline.

And after two years I wanted to leave. Cause it’s a tough job. And with Buddy Morrow, the rule was when people threatened to leave, you’d get a tiny raise. But this time he called me up to his hotel room and he said, I’ll let you go if you promise you’ll move to New York. He said, because I don’t want you being a big fish in a small pond. He said, you need to keep pushing yourself and always play with people better than yourself. And so I always tried to challenge myself. Because of him, I moved to New York, and he even made some phone calls on my behalf to some of his old studio friends from those days. He had done all kinds of studio work. And he really helped me so much. He was the kind of guy that every once in a while I’d call him up and try to thank him and he’d act all gruff. He couldn’t take that. He was like, ah, I didn’t do anything. But he did. I moved to New York. I guess it was 1981 and I’ve been there ever since.

HBK: 42 years. Long time. After that, you really played with a who is who of straight ahead jazz.

KP: I was lucky because that last wave of all those classic players were all still around. So here’s Hank Jones, Major Holley, Gus Johnson, Buddy Tate, Sweets (Harry Edison) – I got to know Sweets very well when we started doing gigs on the West Coast. And Bucky Pizzarelli became like a second father to me. Dick Hyman was a real mentor and a champion of mine. Dick made a point of championing younger musicians that he felt could play. He kind of forced me into doing some studio sessions of his.

It wasn’t so much about marketing as now. Jazz is booked now like it’s pop music. You probably notice all the younger players, and they’re smart about this. They all have publicists and they are sending out massive emails to people all the time, and very aggressive. And I was never a self promoter like that. I just can’t do it. I think I’m gonna play as best as I can. And there’s gotta be some people that like this out there. Oh, I found the three. And keep playing for them.

HBK: Which collaborations would you consider as the highlights of those years?

KP: Working with Hank Jones was one. I guested on one of his records. He guested on one of mine. I did a few tours with him in Japan. And he was such a master and funny too and very kind to me. Cause I’ll be honest with you, my first encounters with every one of those legends, I was scared to death, but it is like a family. And they’ll haze you at first in a fun way and push you and test you. But if they feel you can play, then you’re in the family, you know? With Hank, it was such a joy to play with him. He sits down at the piano just playing one chord. His touch and his sound was so unique.

And many highlights working with Sweets Edison, who fascinated me because here’s a guy who played with Basie in the thirties and sounded as contemporary as anybody. Working with some great singers. You know, I, I got to work with Rosemary Clooney, Joe Williams, Mel Tormé. I was with him for a long time.

HBK: I love Mel Tormé. To me he was one of the best singers of all time.

KP: Yes, unbelievable. I guess he just liked my playing enough. I asked him once, what do you want me to play behind you? He said you do your thing, whatever you want, what you feel like. And I gotta tell you – and I don’t bullshit about this stuff – I honestly never heard him have a bad night ever. And he didn’t warm up, vocalize, nothing. He just had this natural voice. And he was a great musician. He could sit at the piano and play really nice piano. And he was a really good drummer. And in fact, he had one of Gene Krupa’s old drum sets that he traveled with and always would do a feature on that. And then he wanted me – no matter what the song was, “Cottontail” for example – he’d start doing the TomTom thing, and he’d want me to do a Sing, Sing, Sing thing with him.

HBK: I talked to some of the younger musicians here on board and they said, well, these people like Ken or like Benny Green, they are our last link to that history of jazz.

KP: Yes. And I actually tried to do the same thing those people did for me. You know, I tried to work with younger musicians and help them out. I gave away every surplus instrument I owned to students that needed better instruments. I never considered myself a real doubler. I played clarinet, played tenor. I had bass clarinet, baritone, flutes, soprano, alto, they’re all in good hands now. So I stuck to those two instruments.

HBK: A friend of mine who is on the ship wanted me to say hello to you. He can be as sarcastic as you can be. He’s always making fun of me because of my weight increase due to the lockdowns. So he said it’s good that you talk to Ken. He knows how to lose a couple of pounds.

KP: That’s right. <laugh> It’s called the Cancer Diet. I recommend it to everybody. I lost 80 pounds. But I’ve gained 15 pounds again and I’m sure this week probably another five <laugh>.