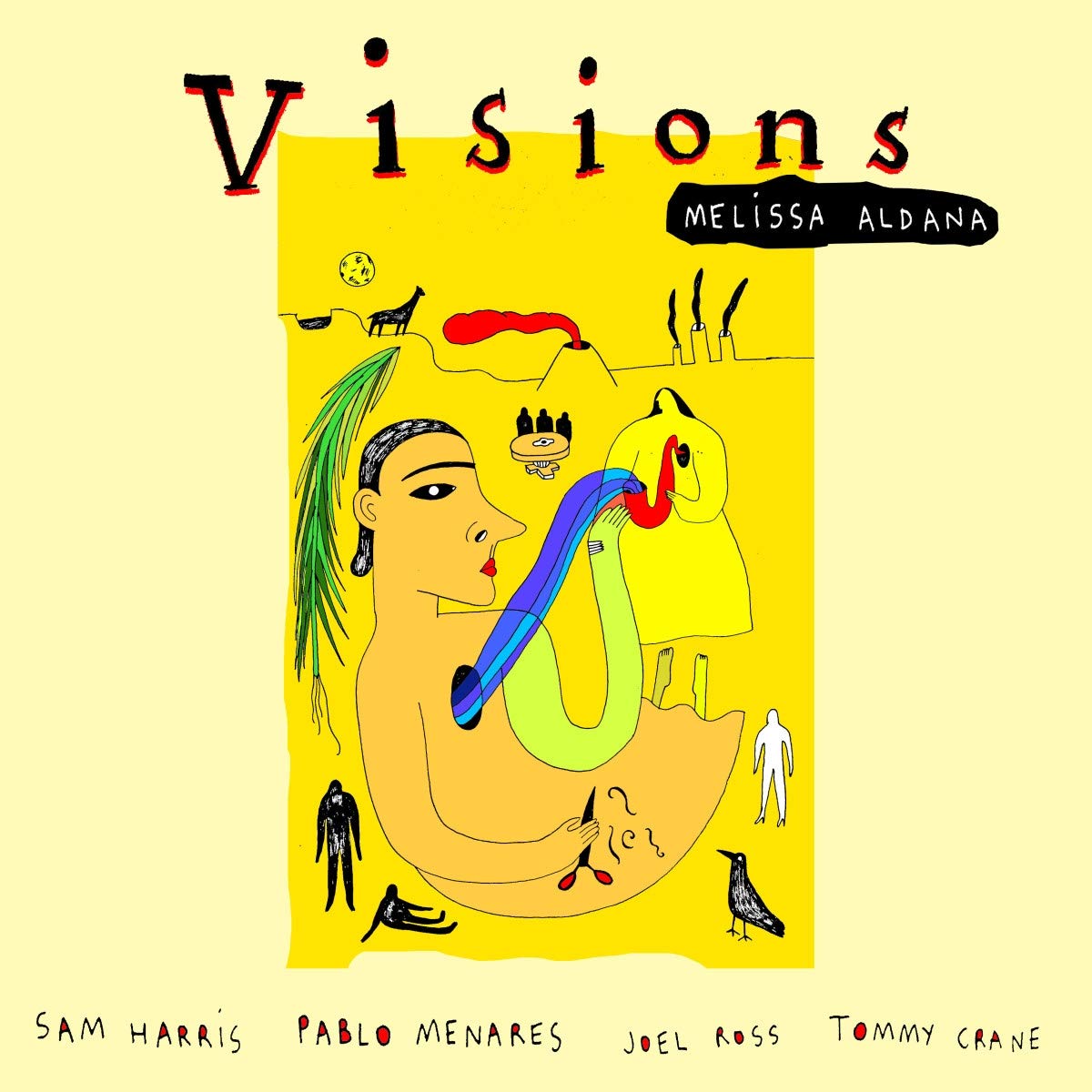

On the Jazz Cruise 2020, Ingrid Jensen played with the band Artemis with pianist and musical director Renee Rosnes, clarinettist Anat Cohen, tenor saxophonist Melissa Aldana, bassist Noriko Ueda and drummer Allison Miller. The trumpet player also performed with the Big Band and some All Star groups. In September 2020 Artemis‘ debut CD was released by the Blue Note lable. On the afternoon of February 5, 2020, we did this interview – before the Corona crisis and the US election.

HBK: Thank you, Ingrid, for taking the time for this interview.

Sure. Where do you live in Germany?

HBK: I live close to Cologne. That’s a very nice area south of Cologne, the Rhine Valley.

I love it. Actually my favorite part of Germany. And the big band. The WDR has never ever invited me to play with them.

HBK: They should.

Put that out there. It would be fun. My sister and I have music.

HBK: For big band?

Yeah, beautiful music.

HBK: There are a lot of people on the boat who book musicians for festivals and clubs. I think I saw the guy who manages the Umbria Jazz Festival.

Yeah, he is here. I know him from last year. It’s almost like you’re in a conference to see everybody play. Yeah, well, that would fit. No, that wouldn’t fit. And you have my records? You have my Kenny Wheeler project …

HBK: Yes.

… and „Infinitude“ with Ben Monder?

HBK: I don’t have that one. I have some of your older ones …

The Enja ones?

HBK: Yes, beautiful music.

Back in the day, man. Those were special, very special projects for me. All of them were very different.

HBK: So maybe we can start in the sequence of events. I know that you were born in Canada, so how did you get from somewhere in Canada into the jazz scene?

It’s a good question and a long answer. Many roundabout ways. My mother was a classical piano player who loved jazz. She had very big fingers, big hands. Her hands were bigger than mine. My dad is Danish, so we have a big Viking bones and she’s a staunch Canadian. So she played a lot of Oscar Peterson and Louis Armstrong and listened to only swing music in our house. That was it. And classical. And Debussy. So it was sort of easy for me when I started playing the trumpet to kind of understand the feel of the music. It wasn’t like I had to go „Oh, how does swing go?“ I was already swinging. I was swinging since I was two. And when I played the piano, I was learning standards by ear, just picking them out or reading from the lead sheets, original lead sheets, because my grandmother and my mom both played piano, and they had stacks and stacks of those originals with the pretty covers.

We had a good music program in our schools. Diana Krall went through the same system. We all were in the Nanaimo district (Vancouver Island). The Jazz band was more important than all the other bands in school, and we found out later that’s really weird. Most programs, they don’t do that. But jazz was like our thing. And so I had a really good beginning. I had my own band when I was 16 playing trad jazz. And then, as I heard more music, I realized I wanted to find my voice in the music and not so much try to copy Louis Armstrong or Clark Terry. Clark Terry, who eventually became one of my best friends and my mentor, and who encouraged me to do that.

He encouraged me to be me every time he heard my sound and my approach to the music. He would say things that I can’t repeat, but it was mostly just like you are making me very excited. He was my big mentor. And he helped me a ton with figuring out my role and my place in the music which was just to be me. Is really what it’s about. And so I went to college. And the last minute after the two years of college, I decided to go to Berklee because of that big scholarship. They gave me more when I got there, and I ended up graduating from Berklee College, went straight from the Nanaimo to Boston and studied for three years. And at the end, I really wanted to meet Thad Jones, of all people. Right? And I was like, I just have to meet this guy. It happened that Thad Jones was living in Denmark, where my aunts and my whole family lives. My aunt said at any time you want to come and stay, you can stay.

So instead of going back to Nanaimo and probably never playing music again because there was no scene, really, I went to Copenhagen and I was there for almost like three months. And then I came to New York for a year and then another three months. And I spent a lot of time with Ernie Wilkins, Clark Terry’s best friend. All these Danish musicians, they kind of just took me under their wing because I was just practicing all the time, transcribing …

HBK: Denmark has always had a great jazz scene compared to the size of the country.

It’s incredible. And when I was there, it was the heyday because it was, you know, Tivoli and Montmartre, I didn’t go there as much as I wanted … Ben Webster … and all these other little underground clubs. And I was playing every day, just jamming almost every day and then practicing during the day. So it was like a luxurious post college experience. And at that time, Ernie, Ernie’s daughter and I became very good friends and she was living in New York. And I finally was like, OK, I got to go to New York. I went to New York.

HBK: Did you meet Thad Jones?

I didn’t. He had already passed. It was so sad. By the time I got there, he had already passed away. So I had to reshape my dream of stalking Thad Jones. And, you know, I was just amazing time in New York because when I got there, I was immediately playing – I had never played with an all women band before. And there was a club date band, I played with them. It was called Kit McClure Swing Orchestra. I was purely swing, women playing swing music in dresses for gigs, for money, not for like artistic sake. But the good thing about it was all these great musicians from New York and one of them said, you know, you should probably get lessons with this woman, Laurie Frank. I went to study with her, and she immediately she laid stuff on me that, you know, was life changing.

HBK: Yeah. She was a great player and educator.

Great, amazing. I played – I couldn’t play the trumpet at all. She heard me play like that back then. She would just be like, no way, that’ll never happen. And she was my teacher. She believed in me. So it was a long road to getting to things being easy on the trumpet. She helped me immensely.

HBK: I think I still saw her when she played with Maria Schneider.

She played with Maria till the end, till she died. She was just an incredible teacher. And that was an amazing time. And that time in New York was when Charlotta, Ernie Wilkins‘ daughter, dragged me down to the Vanguard. She said, Ingrid, you’re going to go sit in with Clark Terry tonight. And I was like, no way. I was so nervous, I just about died. I was like shaking in my boots.

Because I had had an opportunity to meet Clark Terry when I was at Berklee, and he was my idol since I began. And all of a sudden this young guy, Roy Hargrove, came into the school and they kicked me out of the ensemble. I was supposed to perform with Clark Terry that night. Like, „sorry, we got this new guy“. So I didn’t get to play with him in the ensemble or meet him or anything. It was just like „wow, welcome to the biz and the reality of how the music works sometimes“. So I had to wait another three years.

HBK: But you are still here.

< laughing > I’m still here. Yeah, that’s another sad story. But the beauty of it was I think I had a little more together at the point when I met him that he was truly impressed. And from then on he just dragged me on stage everywhere, and we’re talking everywhere. There’s a video of me in Munich from the concert hall sitting in with Lionel Hampton, and nobody knows who I am, because the producers didn’t know that I was going to sit in there. „Right now, she can’t sit in“ And Lionel and Clark were like, „yes, she can“. Like, who’s this blonde girl coming out playing a solo on „Flyin‘ Home“? Here’s no credits. It’s so funny. It’s the great connection there that I was living in Vienna. I got a job teaching at the jazz school in Linz. And so I moved out of New York for a couple of years to make some money and regroup even more. And it was an amazing experience. I played with the Vienna Art Orchestra. I played all this avant garde music I would never have played in New York at the time. I played a lot of contemporary classical and really got my love for Europe.

HBK: Linz is really more classical than jazz.

Well, they had a jazz department, and they hired me and they paid me really well. So I couldn’t say no. I was like, I’m going. It was a very difficult time. I had to learn German. Mein Deutsch ist nicht sehr gut. Aber ich kann ein bißchen verstehen. Und mit Alkohol geht es besser. < laughing >

Anyway, I had to learn the German language partially. And then at the same time Clark Terry’s manager, the manager of the Golden Men of Jazz, he really liked me. This guy, Alex Zivkovic, you might not know Alexander Zivkovic.

HBK: No.

He took a cassette of mine and he said „Oh, I want to get you a record deal“. And I was like, oh, I’m not going to record till I am fifty. He was like „no, I think this is an interesting idea“. So he took my cassette and sent it to a bunch of companies and that’s how I got the deal with Enja. So that’s kind of really, you know, the nuts and bolts of my history. Then it was like I have to move back to New York. I got to start playing with these guys and gals.

HBK: You played with Maria Schneider for a long time.

Yeah, I think I was a big part of the sound of that band. But as all relationships go, things change. And in a way, I really did need to move on to my own projects and small group things. Serving a big band is cool, but you know, I have a child now and she’s eight and I want to be with her. I have to really be selective of what I do and where my time goes.

HBK: Do you live in New York or in Canada?

I live in New York. When my baby was a year old, we decided we can’t live in the city. My husband’s from Alaska. We’re used to this. And we’re like, we need water and trees. We have money for a house? I bought a house, a little bit outside of New York, just north of the city. It’s a 45-minute drive to the city. It’s fantastic.

HBK: Is that in the Somers region?

Sort of, yeah. Westchester, right on the Hudson. We have a beautiful view of the Hudson River … the light. I was so lucky.

HBK: I like the area. It’s almost rural.

Yeah, it is.

HBK: You are in the city in forty-five minutes.

It is so beautiful to not have to be in the city and have a garden and trees with a great backyard, big swing, and we grow our own vegetables, and then we can go to the city and gig.

HBK: You have been doing quite a lot of work together with your sister in both small groups and big band. Is that still going on?

It is. We’re trying to find the time and the means to record another big band record. So we have a whole bunch of music. In the meantime, she’s got her own thriving career and the Artemis thing is filling up a bit of my valuable calendar real estate.

HBK: That’s good.

< laughing > It’s fine. Do I complain? No. Amazing.

HBK: It’s such a great band. I like that sound a lot. I already liked it in 2017 when you played at the North Sea Jazz Festival.

Yeah, that was so new. That was Alison (Miller)’s first gig. Did you know that?

HBK: No.

She showed up at the soundcheck because she had never played with the band. She couldn’t make the first few gigs. We had a sub who was good. But, you know, Alison is …

HBK: She’s amazing.

She’s a band leader. She’s a composer. And she’s a very intuitive force who has, like, huge, huge spectrum of listening going on.

HBK: I heard her with her own band as well at North Sea.

So fun. We’re very lucky to have her. That was my idea, in fact. < laughing> You gotta help out.

HBK: So tell me more about how you came up with the name Artemis.

Oh, well, because the other name sucked.

HBK: It was a bit long.

It sounded like a commercial for some kind of product. Woman to Woman All Stars … you know, it was a sequence of real, I would say, coincidences where first, you know, people were like, oh, a woman band, all stars. It’s is no different than, you know, the Brecker Brothers All Star bands. You know, these guys played with Brecker and they put them together. And sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t. Or Blue Note All Stars. So it was one of those things and it was OK. It was good, strong. But it was not going to be possible for all these people to play together because everyone had their own careers and schedules. And then another tour came together with Cécile (McLorin Salvent) and the group that we have now. And everything just kind of fell into place. And we started all writing and contributing music, which also fits each personality without it being disturbing the waters too much. Artemis – the name itself was something my husband and I were googling. We’re like, what can we do? It’s got to be some kind of goddess. How do we figure that out? So we were looking. He’s has Norwegian roots. We’re like, let’s look at Nordic, Norwegian legends online and see see what’s there. And they were all really bad. There was no woman that you would really want to name your band after. And then we got into the Greek goddesses, and I think there’s a string quartet called Artemis. It’s got that fire in it. Every time I’m playing, I’m like, yeah, we should have outfits.

HBK: < laughing> Yeah. Like the Sun Ra Arkestra.

Yeah. Sun Ra should be an honorary guest in our band. Would be great. We’d just play for free for two hours.

HBK: So what’s the difference between playing in an all-woman band versus a mixed gender band.

Hmm. It’s really not much difference. It’s just people, it depends who is the weakest listener on stage. It’s the same in my own band, which is a mixed band. Our music will be only as good as whoever’s listening and playing on the lowest level. So since everybody’s on a high level, you can do anything. And everyone’s writing and practicing their instrument and researching the music all the time. In the end, there’s no difference. I think maybe Renee said something that was funny. It was interesting actually, the way we in the early days were working things out, we had big rehearsals and we talked about stuff. She said it was very funny how everyone does, they explain themselves differently, like a man would just be like boom boom boom, we have to go and have a little more of an elaborate way of communicating. That may be a thing that affects the music, I don’t know. It’s not elaborate. What is the word I’m looking for? I don’t know it in German. I don’t want to say sympatico, but maybe there is because three of us are mothers. We’re always listening on these levels of different energy communication. It creates definitely a different listening pattern, I think, than with men. Sometimes with men, it can be very aggressive and strong. But it can also have that balance of subtle feminine energy … if they’ve check that out and they’re in tune with it. But in jazz, as you know, it can be extremely masculine sometimes and there’s no room for those openings for subtlety unless it’s been deeply discussed or is the concept of the group. So in that sense, I think sometimes our communication is on a very high level and slightly easier sometimes than having to deal with, I think, through ways of playing that are more masculine … some weird description.

HBK: I thought about that last night when I listened to Artemis‘ whole set. I must say, when I closed my eyes, I couldn’t tell if these were men or women who were playing.

Yeah, well, you can’t hear gender in music. I mean, you can if it’s a voice, it’s a guy or girl. But then again, little Jimmy Scott, he sang and I was like, oh, listen to that woman singing. She’s so beautiful. It’s a guy. It’s a man that happens to have a special condition. Yeah. It’s the same thing with my instrument. People tend to put gender on the trumpet. It’s like, oh yeah, that’s a guy’s instrument. Who says? That’s some old school thinking, so stale and backwards.

HBK: It’s so nice that there are more and more women playing trumpet or other supposedly male instruments these days.

Well, it’s nice of you acknowledging. Part of the problem is that this gets into a very sensitive discussion for me, that I think jazz has been propagandized in little ways as far as the way it looks. Pick up a jazz book from the 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s, 80s, 90s. Most of the time there is a singer, and it’s female.

HBK: Maybe a piano player.

Maybe a piano player … maybe. But that’s an artistic decision of the photographer. But at the same time, I look at it and I’m like, no wonder there’s no women in jazz. They don’t see any images of women playing. You go in a band room. This is one of my big issues, too, as you go into a music room in most schools in the States and in Canada, there’s a picture of Wynton Marsalis. There’s a picture of Louis Armstrong, and maybe, maybe a picture of Ella Fitzgerald … maybe. And, you know, all the Yamaha artists, which are all men, and those endorsements they get. So that imagery has got to change too before we can really feel the music grow. We are the last thing in the music to change.

HBK: My feeling is that the process is ongoing. I mean the fact that you have formed this group now will certainly help.

Yes.

HBK: It will give female instrumentalists more exposure and more attention.

Well, I played with Terry Lyne Carrington,too, and her group Mosaic. That project was the ceiling breaker, like it cracked the glass ceiling as far as women writing amazing music and playing together and sounding like any great band. And so now I think there’s more, it’s easier for the younger generation.

HBK: And it’s great that you can release the first recording on Blue Note.

Yeah. This band is so spoiled. We have great management. We got great photos.

HBK: When you look at the history of Blue Note records, there were not that many women on Blue Note.

Yeah. Did Geri Allen play on Blue Note? I know Renee did. Renee might be one of the few female instrumentalists. That’s embarrassing, but that’s great for us.

HBK: Absolutely.

I have to go back to my story of getting my record deal. I really respected Matthias Winkelmann and also this manager because the manager said „OK, do you have a promo photo? I want to send it along with this.“ I’m like „no, you can’t even tell them. You don’t get to tell any of these people at these record labels that I’m female.“ And the reason I did that was because people had already been trying to, like, dress me up and sell me as some kind of sideshow early on in my career. And I just said „no, if they like what they hear on the cassette, let’s see who reacts.“ And out of 10 record labels they sent it to, Matthias Winkelmann from Enja was the only one who said „I like this guy’s sound, like Woody Shaw“. You know, he had the awareness of the artists that I was checking out, like Freddie (Hubbard), whatever. And then he found out I was female, and it didn’t change anything. He was like „let’s record“. And I’m very lucky that that was the way it was then.

HBK: Those were three great CDs.

Thank you. I should have done more, but I felt like I needed to try to be more independent at that point and make my own projects and own everything, because that was the time that things were shifting into the artist share area. And in the end, you know, I own my CDs. I made all the money back in a year. So it was a lesson for me in the business as far as how that worked.

We have to stay current as well as acknowledging all about the past. Clearly, my mom played me Oscar Peterson over and over. But, you know, to be current as well with the technology that is harder than in the past. As far as CDs go, does anybody really even have a CD player? You can’t even get a rental car with a CD player. I just bought an external CD drive.

HBK: On this ship, it still works.

Thank goodness! At least this audience, they all have CD players. I should have brought my LPs.

HBK: We already talked about some of your idols. You said Clark Terry and Thad Jones. Your recent CD was about Kenny Wheeler. And can you say a little bit about your relationship to Kenny?

I would say it grew out of my affinity for Art Farmer and Booker Little. They are the lineage into my being able to hear what he was doing. And I think because Kenny Wheeler’s Canadian roots, there was some kind of connection there in the compositions, especially. His sound and his whole way of phrasing things so freely, but still playing incredibly around the instrument, around the music, grabbed me once, maybe in my 20s, when I was stuck way into Freddie Hubbard, Woody Shaw, Lee Morgan, Clifford (Brown), all those legends as well. And Clark (Terry), of course. But the modern contemporary vibe that Kenny brings to the language that I think is pertinent spoke to me. I was very lucky to be with him at the Banff school for three weeks. I was just listening to his teachings, his daily playing and his deep discipline about the music, and hours we spent composing. He was very hard on himself. Which at the time I was too. Now, I am more like „ahh, get over. I don’t waste time on that.“ He had a big impact on me. And we were able to do a few gigs together with some good bands in Germany. He was an amazing musician and the sweetest …

HBK: Yeah, he was a nice guy.

… the kindest human ever.

HBK: Recently in our King Georg club in Cologne, we had the trumpet player who in some ways reminds me of Kenny Wheeler …

Who is that?

HBK: You know Ack van Rooyen?

Totally, beautiful. And he’s one of my early sound influences too.

HBK: He turned 90 this year. And it was amazing how he could still play. I mean, he only plays flugelhorn, but just amazing and so beautiful. And he played for two hours, no problem.

Respect, Ack! That is amazing. I listened to him a lot during the early days.

HBK: He had a pretty broad spectrum, right? He played straight ahead jazz. But I also remember him from a European group called United Jazz and Rock Ensemble. It was actually led by a lady named Barbara Thompson, a tenor sax player.

I know her.

HBK: Ack played in it, and Wolfgang Dauner, the German piano player who died recently, and Albert Mangelsdorff. It was a great band.

Yeah. I do remember that band. I may have heard them live. At the Berlin Festival.

HBK: Yeah, could be. They were very popular while they existed.

Yeah. That’s great. It’s really inspiring.

HBK: The trumpet is probably the hardest instrument to stay on top on when you get really old, isn’t it?

Maybe, we’ll see. I mean I’m feeling a little old right now. Over 50, but still doing it. My goal is to make it easier. I’m very lucky I have this trumpet. This is a custom Monette by Dave Monette who makes Wynton (Marsalis)‘ trumpet, and Terence Blanchard‘s and a lot of great symphony players. You may not know his name, but at this point in his evolution of design, his design goes hand in hand with where you’re at with your body. So if my body’s in alignment and everything is working efficiently, the trumpet plays itself. If I rely on the trumpet and I force my body, it all shuts down. It’s kind of magic, kind of voodoo, but actually when you’ve done all the studies that I’ve done, which is thousands of hours of Alexander technique, Feldenkrais as well as yoga, it’s kind of a game changer. The gear he makes is so efficient and so modern, so perfect. It makes the old trumpets look a little bit in need of being retired like I have. I have an older vintage horn that I play on sometimes, but I use modern mouthpiece equipment, which makes it easier. That’s really my secret. If the gear is not working now, I’m going to get tired. And if I’m not playing efficiently, I’m going to get tired. So even if I’m showing up exhausted and not feeling great, if I just put myself in the right posture with the instrument in the right alignment, all I have to do is add some air. It sounds simple and kind of I sound a little snobby. But it’s really true. I have students at Manhattan School and Purchase College. And all of them, with these little adjustments, micro adjustments I do, thanks to Dave Monette, they all play well, they all end up having more range, more endurance, and they don’t have to stress so much about getting to the trumpet. So it’s kind of – I call it – an urban legend at this point that the trumpet is hard. It’s been kind of misinterpreted and poorly taught.

HBK: So with the right trumpet and the right technique, you can play till you are a hundred?

It’s the tax man that’ll get you if not the cancer …

HBK: There are not that many trumpet players who really stay on top when they, let’s say, pass 80.

Clark (Terry) did it, Clark played well till he was 90. And Clark Terry was one of the most in-shape humans ever. He didn’t drink a lot. He didn’t smoke. He smoked when he was younger. He had weights. When I met him, he was 70 something. He had weights in his room. He’s lifting weights, being trained like a boxer until his body finally gave out. And so at 90, he was still playing. I saw him at Carnegie Hall when he was 89. I was like, damn. You know, there’s a certain posture, you have seen him, tense and tight. I wonder how long that’s going to last.

HBK: We have a guy in Europe, he’s from Serbia. You may know him, Dusko Gojkovic. He lives in Germany, in his late 80’s now. Great trumpet player. I remember the first the first trumpet player over 80 that I ever saw was Doc Cheatham.

Oh yeah. Doc kept playing. He was like a hundred or something. I saw him at Sweet Basil’s playing great … You are taking me down memory lane.

HBK < laughing>: You mentioned Woody Shaw. Has Woody also been an important influence for you?

A big influence as far as painting outside the lines, but still knowing exactly what color you’re using. It was a master of harmony. He really had a deep understanding of harmony, melody. I love to play piano. And I spent a lot of time kind of figuring out how those sounds in the upper structure and more angular inversions of chords are trying to work against each other and still create melodies. So he was the master of that, all his compositions were great and very fluid and very logical.

HBK: Tragic life …

Yeah … but thank God we have all that music to be inspired by, especially that Vanguard record, live at the Village Vanguard, „Stepping Stones“. I mean, that’s some of the most incredible trumpet playing. The way he did it deep inside the changes and is able to create such tension and release while still really maintaining the integrity of the chord. That’s what we all want to do, we want to have freedom. Jazz is about freedom. So to find the language of another world but still be within the tradition is the challenge.

HBK: You have spent quite some time in Europe and in Canada and in the U.S. How would you compare the jazz situation?

The jazz situation … when? Now?

HBK: Yes.

Like today? I think we are in a big dilemma in the United States because of our political situation and it’s going to take the arts down with it. We have an oligarchy, we have a dictator. We have someone running things behind the scenes. He‘s being puppeted by even worse people in what he appears to be. And the arts are irrelevant, are absolutely unnecessary. In fact, they frighten those people because the arts and the artists have individual thought and therefore we’re screwed because there’s going to be no funding and there’s going to be less possibilities for people of lesser means to have their art and the music supported in places where people can come in hear and see it. And that’s frightening. Canada: So I got a Canadian passport. I’ll get out of here as soon as I can. Norwegian roots. Maybe we’ll go for that passport, too. No, it’s I’m sorry, but it’s always a relief to go across the sea at this point. I was in Switzerland two weeks ago. And it was therapeutic to be around that kind of support for what we do.

HBK: In Germany, there is quite a bit of public funding for the Arts.

Canada too. You can get grants to do anything in Canada. The States has some grants, but what I’m talking about it’s more the environment now that is being created because of the assault on education. It’s not a lack of funding on education. It’s an actual assault. There are states in the United States that want to get rid of public school because they don’t want people coming in with free thoughts. And I sound like a propagandist, but I actually know this firsthand. I’ve seen it. I’ve seen that. I have a friend who’s a band director from Arizona who literally took his family uprooted and moved to Europe because he got a job that paid half as much as he was making, but he felt like he would be safe there, that he could do his work, got to share improvised music with people who would appreciate it. So, you know, not to get too dark, but it’s where we’re being held hostage by a situation that is all about big, big, big, big money, making huge money, beyond money. And those of us who don’t have it, we’re just little flea’s on top of the dog, they want to get rid of.

HBK: What I just can’t understand when you talk to people on the ship I would say 95 percent would not vote for Trump. So how could he get the majority. I don’t know.

He’s in bed with some amazingly powerful people. And there’s probably more that have come out of the woodworks since he became sort of a figurehead for this manipulation, this destruction from the climate, from the earth to to the arts.

HBK: Yeah, but still I mean it’s a democracy. He needs to get the votes, right? And there must be a hundred million people who voted for him.

Young people vote! Young people vote! People in Germany who read this, call your Facebook friends, tell them to vote. That’s all we got at this point. We have to just hold on and hope that there’s enough information that seems real, that’s also the assault. Jazz, look at jazz. It’s one of the last things you can do without any kind of computer formatting. Like you don’t need an iPhone to play jazz. You don’t need to plug anything in. You can just start improvising.

< listening to the music in the background > Listen to this … perfect. Trump would hate this, anyone that likes Trump would hate this. What is that? What’s this for? What purpose does this serve? … I love Europe. Europe, I love you! Bring me back. I love saunas, I love education. I love people who show up and just listen for the sake of listening. It’s actually probably the real secret why I’m here. It’s when I lived in Austria, those two and a half years, I came back to the States with a feeling of validity. I was valid. I had been validated by different scenes who appreciated what I do. They didn’t care that I was a white girl from Canada. They’re just like, wow, you’re trumpet playing, and your writing and your music makes me go here or there. And then the musicians at the same time are also very supportive. So to come back to the states and have to deal with this beast that has been unveiled by Trump, somehow I was prepared. Europe and my experiences with culture and appreciation for an even culture without this super rich and super poor made me realize, hey, man, I think I could do this, you know, between Canada and Europe, I think I can stay afloat and present things that I’m creating.

HBK: I’m sure there could be other opportunities for you in Europe in terms of of teaching and playing.

Sure. Believe me I get offers. But at the same time, there’s something about staying in the battle. My husband is from Alaska. He can shoot a bear. He has a gun licence. < laughing > He’s amazing, but he also swings a lot on the drums.

HBK: He’s a musician?

Yeah, he’s a great drummer. He plays drums with Darcy James Argue. He’s also Geoffrey Keezer’s drummer.

HBK: What’s his name?

Jon Wikan. He‘s absolutely fantastic. Okay, you know, I’m biased. He’s my husband, but he really is good. But we’ve decided to raise our child in a community that starts from the grassroots. We are friends, best friends with the mayor of our town. And we started a pub in our town. We have built and funded this local brewery to create this community that can at least meet together and have a good place to hang out and make music. So in that sense, it’s like we get to survive the craziness of the United States in our little bubble. But we also can slowly have an effect on our community. And apparently that’s – in the big picture – that’s apparently how it all is going to change from the bottom up, not from the top down. So I’m very fortunate, again, to be in that situation where we can have amazing friends and have our child in public school and meet these different people with different cultural roots, people from Ecuador and Peru and immigrants, and then rich white people and just have some kind of a meeting place. So it’s pretty cool.

HBK: Artemis is nicely mixed, right? You have different countries, different races …

… different ages …

HBK: … different ages. Absolutely.

That is the craziest part, you know, we have almost someone from every generation. We need a teenager. No, we don’t.

HBK: < laughing > Melissa (Aldana) looks like one.

She’s 30. She finally made it.

HBK: What’s your view? Is race still a topic in the jazz world?

What is that new phrase everybody says? I forgot how it goes. You know, borrowing from other cultures to do your thing … I never thought about that when I was young. I just heard music, and not everybody was allowed to play it. That’s how it goes. First, when I moved to the States, I realized, because they never resolved racism and they never took care of reparations and the things that are really important. There’s a lot of political and other aspects that create a division. Until there’s great leadership, which Obama did provide for a while, he brought calm and a peace and a conversation to it all.

HBK: And then came the backlash.

And then came the backlash. So maybe if we can recover from this, the conversation will continue.

HBK: Well, my question was not so much about society as a whole and more about the jazz world.

In a nutshell, Clark Terry was my mentor. Clark Terry, if you read his book – and anybody who has not read his book you have to read his book – it’s amazing, his autobiography. One of the first things he ever said to me was the note doesn’t care if you’re blue, black, purple, green, yellow, midget, giant. The note cares about the heart behind it. The music happens as a result of the heart behind it. So he never saw me as a white girl. He just heard me play. He was like, oh, you’ve been checking me out. I mean, one of the biggest compliments he ever gave me was „Ingrid, you ever meet pops?“ I said no. „ Pops would have liked you“. I was like, wow, I was stunned. I had never thought about it that way. You know, it was like, oh, let me have some orange and some water, let me digest this food. And part of who I am, a little swing, a little funk, a little whatever I’m into. So the men that I grew up with, Harry Sweets Edison, Art Farmer, Lionel Hampton … I don’t want to forget anybody … Al Grey, even Benny Golson. When they heard me play, I think their eyes were closed. So for me to come up with them and have their endorsement was huge. And not only their endorsement. It was like if they saw me from across the room, it wasn’t like, oh, Ingrid‘s here, it was more like, you, on stage now, trumpet out, play. I mean, how cool is that? It’s like you can’t pay for that. There’s no education in that. That’s just real people being nice and sharing the music. I never really had to really think about it so much that I had to prove anything. It was more you gotta do the work so I can become more who I am on many levels. There’s mental health work as much as there is trumpet health work, music composition and transcription, analysis.

HBK: I’m thinking of a guy like Nicholas Payton with his Black American Music …

… which I actually think he’s onto something. I’m actually starting to feel I was a little offended by it at first, but I think many of us have misinterpreted what his message was. His message is to give it credit where it came from. And I don’t know enough about it to be quoted on it, but I’m not opposed to where he’s coming from because I think he has a valid perspective on what the music is. If jazz was slang for something negative back in the day, then it’s kind of a drag. If you’re black and say „hey, man, where is jazz coming from?“, I get it. I want just good music and rhythms that come from culture that we were fortunate enough to share, cultures we were fortunate enough to share, and which is the invention of counterpoint and the instruments and the music and the harmony and the melody in the middle. It’s a very big conversation. It’s a very difficult conversation.

HBK: My understanding was when he published this there was some idea behind it of segregation as well.

I don’t think so. He recently came out and was trying to clarify. And I think Sean Jones is someone you should talk to. Sean Jones and he had a great conversation about it. And Sean is on the forefront of jazz education right now and making it even, not like one thing and the other.

HBK: He was supposed to be on the ship.

I know. What happened?

HBK: I don’t know. Somehow he dropped out.

Yeah, it’s so weird he’s not here. I told somebody he was going to be here. He was like „can we hang out?“. He’s so busy. He’s got so much on his plate.

HBK: I think he was appointed to a new position, an academic position.

Yeah. Peabody. He is making big changes there, he’s making changes everywhere, you know … not changes. He’s just opening the dialogue. And I feel like maybe this is the good stuff that we got from Obama. There’s no support in some of these institutions that have been so completely led by white men over the years, classical conservatories, for instance. And now they’re realizing they’re going to go down if they don’t open up their views as far as the way I spoke about. Oh my God, the music is going to win, that’s for sure. The audience is going to win. It’s a win win all over. Let’s start to break down some of these barriers.

HBK: Terrell Stafford is the dean of the music department.

He’s amazing, too. He’s another guy who I don’t think he sees color when one is playing. When we are going out together, we are just talking trumpet. And it’s a beautiful camaraderie – we as people who have done the work and are just trying to say something from themselves without restrictions.

HBK: So now we have spent quite a bit of time on Artemis. What is in the future beyond Artemis?

It is a good question. I got to find some time. I’m kind of booked a couple of years ahead.

HBK: Really? Great!

My life is very full. I do a lot of things as a guest artist. Playing my and my sister‘s big band music. And those are really great opportunities as well because some of these schools have me in after 35, 40 years of having guest artists. I’m their first female artist. Not that that’s why I get the gig. But it’s a nice change. I think it’s also part of the opening of the conversation. So I do that, and I try to balance things with my teaching at the two schools I’m at, creating a composition class at one of the schools, which is really fun. And being a mom, that’s the biggest balance, is making sure I have time to parent my child. And so saying no sometimes feels really good. Hey, you want to do this? No … I’m going to go hiking with my kid and go shopping afterwards. It’s a good place to be.

HBK: Well, thank you, Ingrid. It was a good talk.

It was great. I think we solved all the world’s problems.

HBK: Absolutely.

We need a new president and – that’s about it. We get rid of Trump.

HBK: Good luck for the next election.

I’m glad I joined a wine club. They send me a box of wine every month.

< both laughing >

HBK: That is also a solution …

… and I’m glad we built a brewery too … Danke schön!

HBK: Ingrid, thank you very much. Take care!